Lend Me Your Ears…

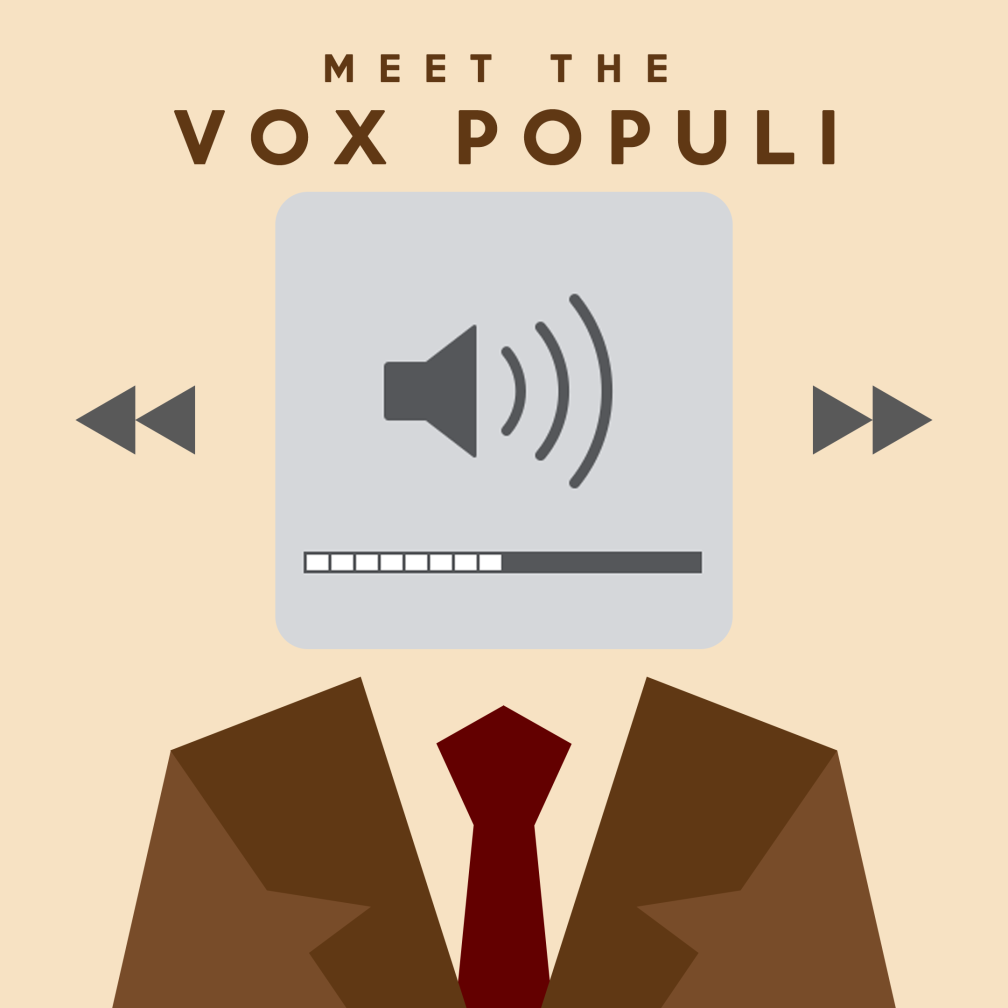

My first image began with the idea of creating a statement about modern society’s relationship with technology as a sociopolitical force, exploring ideas pertaining to digital communication and its effects on self-expression. As discussed in Week Six, the advent of digital technology and social media in the past two decades has led to the emergence of ‘one-to-many’ or ‘many-to-many’ communications as the dominant form of media in contemporary society (Jenkins, Ito, & Boyd 2015, pp. 1–4). This contrasts heavily with the information flows of ‘many-to-one’ that accompanied the birth of mass communications in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The society which we now find ourselves in is the reversal of this paradigm: ‘control’ of media discourse (if any such control could be said to exist) now lies in the hands of the entire digital population—in some ways this could be interpreted as the ultimate form of direct democracy, where each digitally present person is allowed a medium to communicate their own opinions, complex thoughts, and ideas, with the possibility of collaboration and discussion also present.

However, this capacity for discussion also raises concerning points about the quality of sociopolitical discourse—contemporary political spheres now place great emphasis on social media, even though such media has become a hotbed for opinionated and anti-intellectual exchanges. If this is the ‘vox populi’ of the modern world, it has been irreparably changed by the introduction of social media—and not necessarily for the better.

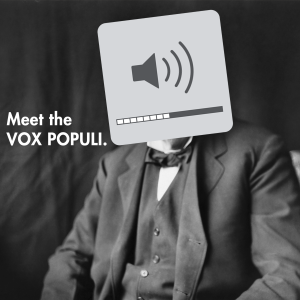

It was this concept of the ‘vacant vox populi’ that I intended to convey with my image. In keeping with the themes of popular culture and talking/listening that I kept in mind, I had the further idea of creating this image in the style of an album cover. In this vein, I envisioned an image of a famous figure, ‘defaced’ by some form of digital symbol—in a manner similar to Green Day’s album Nimrod (1997), which ‘de-faced’ black and white images with a yellow circle and the album name.

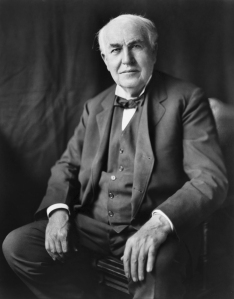

After consideration, I settled on Thomas Edison—the inventor of the phonograph, and thus, modern reproducible music—and attempted to manipulate the image using a volume icon, captured from my own Apple iPhone’s interface. This initial attempt proved somewhat successful but overall lacking, and so I decided instead to create the image in the minimalist style—playing on the semiotic significance of symbolism and representation in daily life (as discussed in the latter weeks of the subject which focused on image, type, and the ‘visual turn’), particularly in an era where icons and symbols have come to dominate human interactions (e.g. traffic signs, emojis, graphical user interfaces for digital devices).

The ubiquity of symbolism is a concept which my final product attempts to subvert: the central placement of the volume icon and the presence of forward and backward playback symbols disrupt our common perception of these images as built-in aspects of our interactions with digital technology. This became especially apparent to me after I showed the image to one of my peers and they mistook it for an actual volume notification.

Overall, the image conveys my sentiments about the current state of digital discourse—we find ourselves at a point where humanity has faded into the background, as shown by the invisible ‘everyman’ figure of the image; displaced by a slew of devices which keep our lives in motion, at the expense of taking over our lives.

References

Thomas Alva Edison, three-quarter length portrait, seated, facing front, c. 1900, photographed by L. Bachrach, Wikipedia, viewed 16 October 2016, <https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/9d/Thomas_Edison2.jpg>.

Bate, D. 2013, ‘The Digital Condition of Photography: Cameras, Computers and Display’, in M. Lister (ed.), The Photographic Image in Digital Culture, 2nd edn, Routledge, New York, pp. 77-95.

Green Day. 1991. Nimrod. Recorded March–July 1997. Reprise Records.

Jenkins, H., Ito, N. and Boyd, D. 2015, Participatory culture in a networked era : a conversation on youth, learning, commerce, and politics, Polity Press, Cambridge, UK and Malden, MA, pp. 1-31.

Lupton, E. 2010, Thinking with Type, 2nd edn, Princeton Architectural Press, New York, pp. 85-100.

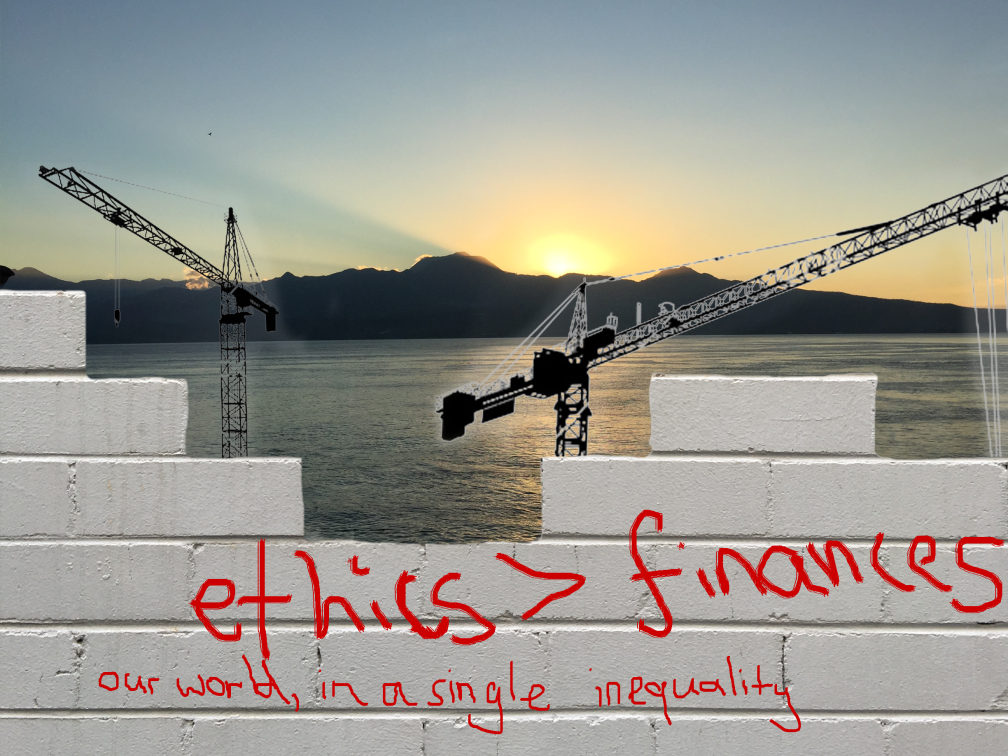

Building Your Future: A New State of Mind

After completing my first image with its minimalist graphic style, I resolved to create my second image as more of a traditionally manipulated work, altering and synthesising photographs of my own making to create a photorealistic composite. In this image, I wished to explore the interactions which everyday people have with the City—an umbrella term which here pertains not only to the built environment of metropolises such as Sydney, but also to the social environments that such physical settings present, and which are sometimes reflected in the media and communication forms that exist in these spaces.

As Hoggart (in Hartley 2009) and Rennie et al. (2016) discuss in their respective works, media and mass communication can sometimes act in ways contrary to their perceived purpose as all-inclusive distributors of information; in fact, they can commonly act as exclusive forces which selectively disadvantage demographic groups. With this in mind, I had initially considered taking a photograph of a beggar in or around the tunnels of Central Station—a location where many of them are passed by or ignored by commuters. However, further consideration of this idea raised many ethical issues regarding the granting of consent and the establishment of identity for any subjects of such a photo, and so I decided against this concept.

Keeping with the theme of social commentary, I instead decided to present a message similar to what I originally envisioned in the above—a work which reflects on the manipulation of messages through media in urban environments. I decided to satirise the ongoing campaigns by the NSW State Government and the City of Sydney Local Government which promote their focus on construction and infrastructure growth, with slogans such as ‘My Sydney: Tomorrow’s Sydney’ and ‘The New State of Business’.

I manipulated an image of a white brick wall and placed red text upon it with what I perceived to be a relevant socieoeconomic message; the aesthetic of this was heavily inspired by the album cover for Pink Floyd’s The Wall (1979). For this reason, the text is drawn by hand in an attempt to emulate the appearance of graffiti. The wall itself was the first part of the image to be manipulated, using a rough and manual eraser to create a rugged feel for the edges of the bricks.

Behind this wall, I placed an image which I took while on vacation in the Philippines; a sunset over a mountain which is intended to signify the natural paradises that once existed outside of cities and the built environment. Between this backdrop and the wall I placed silhouetted cranes (sourced from Creative Commons) which are positioned as if they are constructing the wall—in this sense, the image presents the notion that society is building walls between us and our goals and desires; almost as if imprisoning us within its frameworks.

The cranes were originally taken from a photo I had captured in Lane Cove. I first corrected for the perspective of the photo, but during the process of manipulation I found it too difficult to remove the blue background of the cranes, and so instead decided to use the publicly-sourced silhouettes in the final version.

References

Hartley, J. 2009, ‘Repurposing Literacy’, in The Uses of Digital Literacy, pp.1-38.

Pink Floyd. 1979. The Wall. Recorded December 1978 – November 1997. Columbia Records.

Rennie, E., Hogan, E., Gregory, R. Crouch, R., Wright, A. & Thomas, J. 2016, ‘Introduction’, Internet on the Outstation: The Digital Divide and Remote Aboriginal Communities, pp.13-27.

Transport for NSW 2016, Tomorrow’s Sydney, viewed 20 October 2016, <http://mysydneycbd.nsw.gov.au>

You must be logged in to post a comment.